Vava Dudu

Caresse

Jul 2 – Sep 10, 2022

Opening: Saturday, July 2, 2022, 3 – 7 pm

Go to FB event

Vava,

from your place at night, you can see sparks fly off the railway tracks. Before our eyes, stocky men rhythmically weld metal. We’re in your atelier, by Montparnasse station – the window overlooks the railway line and it’s the one that’s being repaired by men with headlamps, in bright orange clothes with reflective stripes and welding masks. The trains have stopped running, making way for the workers – and we are watching them.

We are in the basement, below the level of the tracks, on the other side from the glass wall, facing the embankment that protects us from the trains. In this room, we take long steps over boxes of clothes, archives composed of fabrics, witnesses to all eras from the 1980s to the present day. There are unusual things, such as your gorgeous Moschino bag or a Kodak bag shaped like a package of photographic film – all items you’ll want to look through again one day. Boxes climb high up the wall; they’ve lined the entire basement. There’s a lacquered, inlaid 1960s-style sideboard and that stunning pure wool rug that Léontine brought you as a gift for your delicate feet. That’s how I found out that “Léontine, the answer is yes” brings you soft rugs or juice squeezed from an orange to boost your morning concentration. I like your feet, Vava. You can wear both number 36 and 44 on them. Your classic is to wear your highstockingspantsboots, but recently you’ve opted for something on a higher technical level: nineties-style Adidas Reebok Instapump shoes. They have small pumps in the upper with which you fasten the shoe on your foot. You’re not particularly interested in fastening them, so you’ve cut off large chunks from the shoes while retaining their mechanics.

Boxes have been replaced by polypylene bags from Tati’s. You eventually had to invest in some sort of a system to organise your archives, but a long, long time ago, everything lay jumbled up just in those bulky bags. Ah, those famous bags of poverty, symbol of instability... Bags of people who flee or travel with almost empty pockets. In France, they are commonly called Barbès bags, not only because the large Tati shop where they were given to customers was in Barbès, in the north of Paris, but also because it is in this neighbourhood that French people of Maghrebian origin, Algerians, Afro-Europeans, new arrivals and refugees without shelter live... Migrants. Everyone’s life is in those bags that get hidden in manholes. These are the treasure bags of street traders. In summer, it is with these bags, full of wonderful gifts, that people load up their cars all the way up to the ceiling to set off on the sunshine trail, leading to the other side of the Mediterranean. These bags, companions to all disastrous relocations, are a theme as broad as a river, which can be encountered in many artists’ works, such as Matali Crasset, Azzedine Alaïa or Azzedine Saleck.

Do Ukrainian women coming to Warsaw with a baby in their arms have Tati bags? Agnieszka, a friend of mine who is a volunteer working on the border, told me that the women she hosts stand out with their beautiful nails and great hairstyles. They take care of their appearance so as not to worry the children. They brought with them only a few necessities in plastic bags. You know, my grandmother, who was a gulag survivor, was obsessed with plastic bags. She collected them and folded them like precious clothes. There was a time when she sold them at the market. Or was it someone else’s grandmother...? Or maybe one of my aunts? I can no longer remember who exactly was selling these rubbish bags to make a little money. Polish grandmothers also survived a war. A different one – but somewhat the same.

But let’s go back to you, to the edge of the tracks, where a chaos of clothes and sketches has spread from ceiling to floor. You had a plan to set the bathtub downstairs, in the kitchen, with a stunning view of the iron road. We open the glass doors and settle down with rum in hand, palm leaf straws and umbrellas in our glasses. Our heads are spinning and our hearts are beating harder – calmed by the rattling of the carriages and the slight vibrations caused by the passing trains. Léontine laughs like a little child. I feel as if you have dressed us all up as railway welders, in bright yellow, like yellow waistcoats, in orange clothing visible from a distance, like fire protection suits. Whenever I wear your clothes in public, I am often accosted by passers-by asking for directions or information about trains or the metro.

The staircase is buried under a pile of bags and boxes. Today they are hardly visible. You don’t use them anymore – neither for ascending nor descending. The bottom floor is closed – your sketches, clothes, and poems live there. We no longer have access to the railway line. We are upstairs, on the ground floor, in your open room. This time it’s a small but spacious loft, right in front of the trains. The centre of the room is dominated by your round, emblematic bed. The one on which the bedding turns when you sleep on it. I imagine Léontine’s legs sticking out beyond this bed, even when he’s lying in the middle, stretched out between midnight and six o’clock – they stick out like the hands of a clock. On the right, you have placed the painting you got from me. It depicts two young people, Afropunks from Baltimore in melancholic poses, wearing white Malcolm X t-shirts, against a purple background. It comes from when I was in Brooklyn, from a time when boys were fed up with police violence. It was then, in 2015, that further protests by the Black Lives Matter movement took place. The painting leans against the window; you hang things on it, sometimes a bag, a belt or a necklace. You can see the trains in the background – this is the perfect composition.

Vava, you are characterised by the feverish energy of an artist who never sleeps. You work tirelessly, there is no separation between you and your art. It seems to me to be something natural in outstanding artists. In fact, I’ve never understood why some people try to separate the “human being from the artist”. Isn’t that what the role of the artist is – to be an absolutely indivisible whole?

On this round bed, you sit and write, weave, cut, and sew. Japan is waiting for you; you finish one small shipment after another – Léontine goes to mail these little packets of treasures. You laugh out loud, but also, to exist fully solely through poetry is a living hell. I know that we feel the same way - that sometimes we would prefer not to have a body and to be just a poem, just an image. According to Jonathan Meese, it is an existence under the dictates of art. It is an uncontrollable tyranny in which we become an instrument of something greater, something transcendent. We are always swinging from one extreme to the other, and when we wake up from the whirlpool of madness, like wild horses racing against time, it always comes down to the obvious: the artist needs their body to create. The artist needs their back, legs, arms, breasts, buttocks, eyes, head, and tongues on breasts, knees on heads, feet on stomachs. Léontine is your love. You find him on the round bed from midnight to noon, between midnight and six o’clock. You find your spirit when you become a drawing and when you finally stop drawing – for a bit. You become a caress. You find value in a person.*

Time to leave your room, this time through the main door to the flat. What stands before us is this wonderful city where children play in yards and families lead noisy lives. Scooters, a game of football, the smells of food from the countries that France marched through with guns blazing. Who would have thought that in the basements of blocks of flats in poor neighbourhoods there would be brilliant artists, living in their beds like Tracey Emin, attached to the walls like moths as Francesca Woodman, crawling on the ground like Pina Bausch’s snails, weaving extraordinary cocoons from tangled bodies.

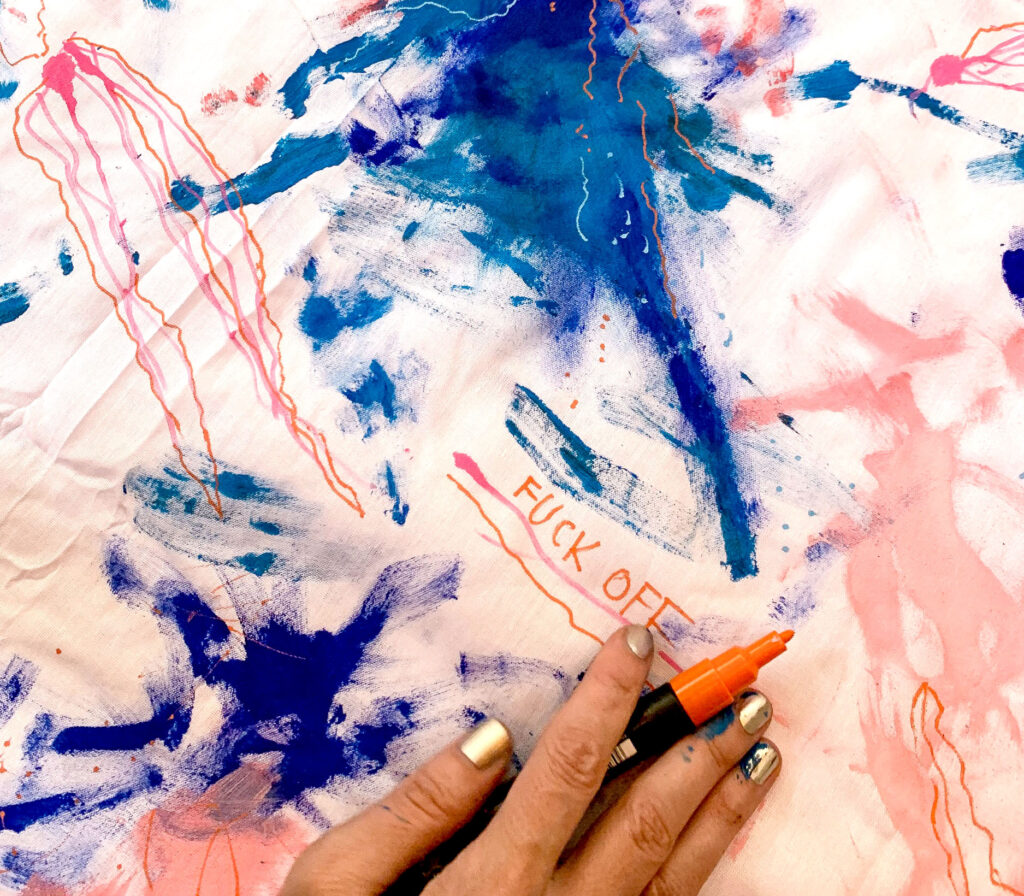

When you get on the train at Montparnasse station and the train starts and the ragged rhythm still rattles quietly, you pass your atelier. In the escaping landscape, the large fabrics in your window are striking – like sails on a ship, covered in paint, with tongues licking skulls, with fingers dipping into holes. You are sitting on the train next to me. Léontine took the seat opposite, Azzedine to his right. In the middle of the conversation you suddenly take out a pair of scissors and cut out a heart on your chest. Your t-shirt transforms into an evening gown that you create on yourself, right here in this perfect atelier – a train compartment. The train takes us towards another train, and onwards from Gare du Nord to Berlin Hbf station, and from Berlin to Warsaw.

Everywhere in the press, one can read that you started very young – with a collection of garments made of waste materials, that you won many important awards, collaborated with Jean-Paul Gaultier, dressed Björk, Gaga, and so on, that you are the queen of the underground. Your band is called La Chatte – The Pussy, because everything starts in the pussy, everything flows out of it. You shout at people running after trains you are not on.* You often have exhibitions in the most famous institutions – from the Berghain Club in Berlin to the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. You miss a train, get on another, wander around Europe to meet children who are waiting for your upcycling classes and other workshops. And you make ball gowns out of plastic bags, which my grandmother – or maybe someone else’s grandmother – thought were valuable material.

Apolonia Sokol

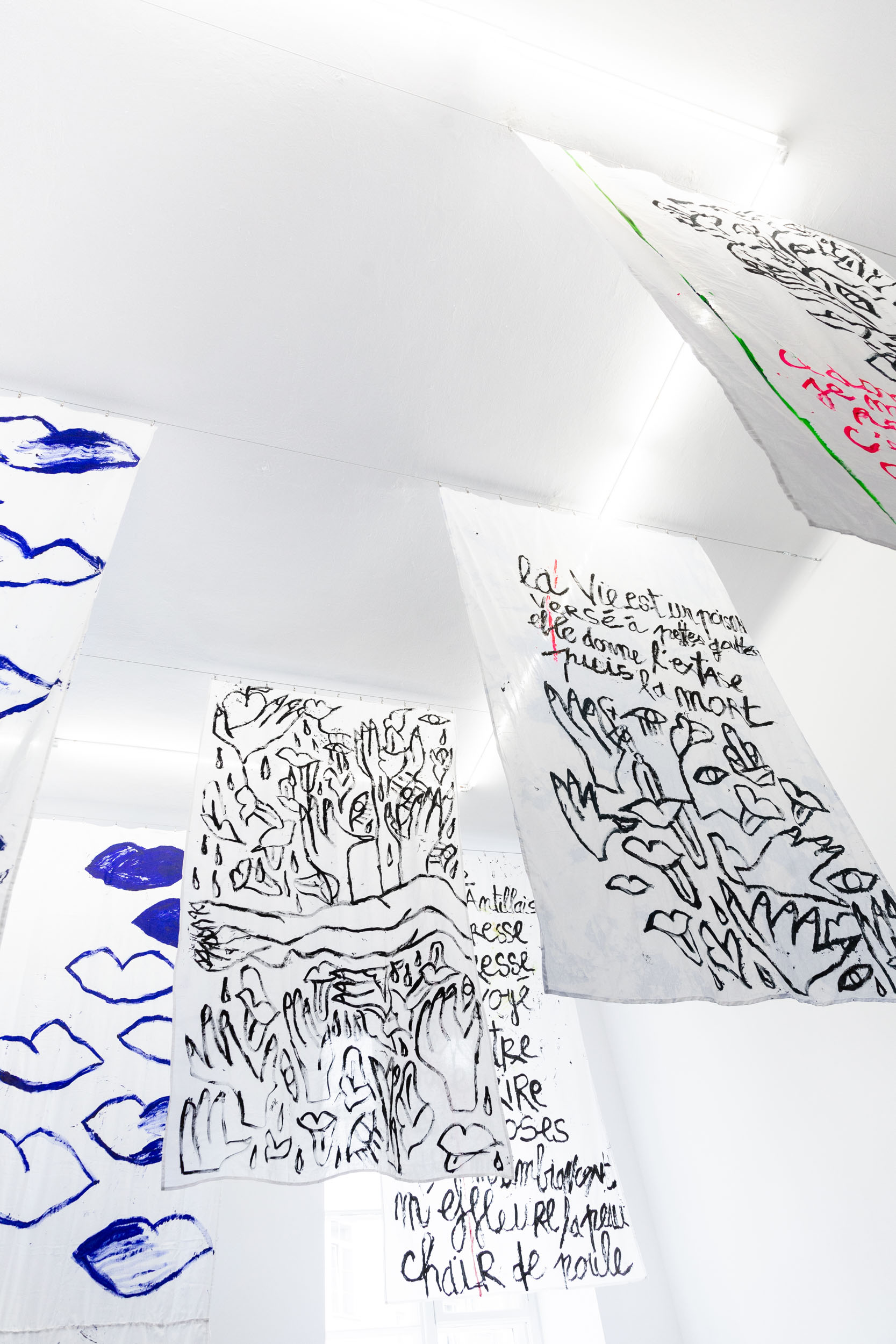

Gunia Nowik Gallery is pleased to present a first exhibition by Vava Dudu in Poland. Her one-room installation is based on the works that will be created especially for the gallery space in Warsaw, fitting into the spontaneous model of the artist’s practice.

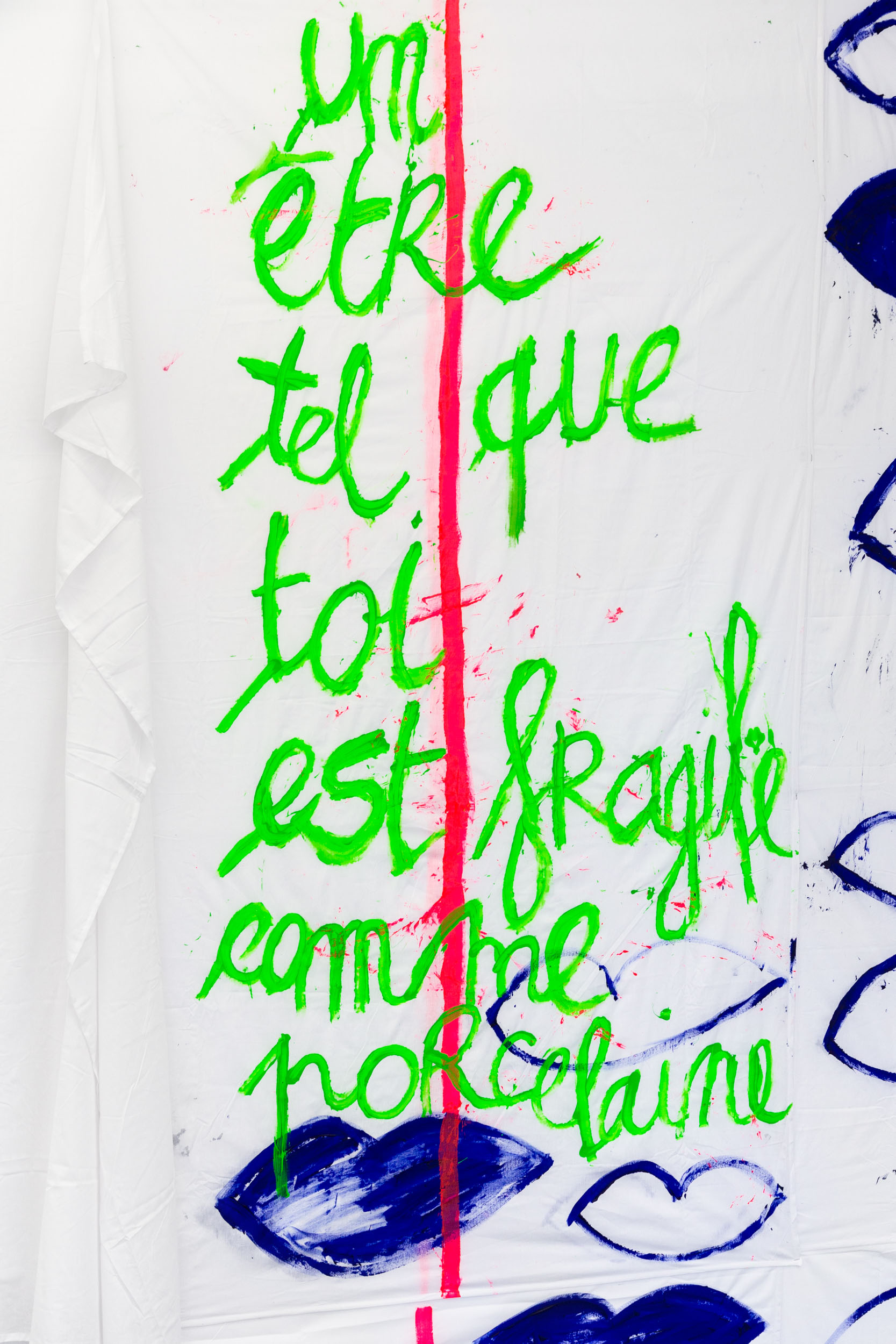

Parisian polymorph artist Vava Dudu (born in Paris in 1970) similarly repurposes the spaces of visibility she encounters. Her work is infectious and auto-generative, spreading by iteration and variation. Growing up in Paris in the early seventies in Martinican a family, she quickly rose to prominence in the fashion world with her upcycled pieces. Her first designer job for Jean-Paul Gaultier in 1997 led to her winning the prestigious ANDAM prize after teaming up with costume designer Fabrice Lorrain. Remaining affixed to no particular milieu (she prefers the extremes of the word; milieu in French means both a social environment and “middle”), she quickly added music to her art, as a member of electro-punk-zouk-neo-wave group La Chatte (Pussy) since 2003. It is poetry above all, though, which through drawing and painting, stitching and lyrics, acts as a catalyst for her multifarious practice. A meta-layer of sorts, her phrases and symbols aim at spreading out over all possible surfaces. [Spike Magazine]

Vava Dudu has collaborated with Bjork, Lady Gaga, Marilyn Manson, Neneh Cherry, Kate Moss and John Galliano. Her work has been presented in major exhibitions and performances, including Palais de Tokyo (FR), Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris (FR), Fondation Galeries Lafayettes (Fr), Le Confort Moderne (FR) and Komplot (BE).

Vava Dudu

Fashion Workshop

On the occasion of the exhibition Grażyna Hase. Always in Vogue at the Museum of Warsaw and Vava Dudu’s installation Caresse at Gunia Nowik Gallery, a workshop with the artist was organized in cooperation with the Museum of Warsaw Foundation. During the meeting, Vava Dudu shared the story of her own creative journey, and the participants learned different techniques of upcycling fashion to then create their own projects under the eye of the artist. The workshop was organized thanks to the support of the Museum of Warsaw Foundation and the French Institute in Warsaw.